It’s late summer in San Diego and you’re spending the day at the Del Mar Racetrack. You’re not much of a gambler but the sun, the cocktails, and the excitement of the crowd puts you into the betting mood. Again, you’re not much of a gambler so you’re only going to place a $2 bet on the next race to “get a taste of the action.”

While you’re in line I ask you how well you think your horse will do? You hedge your answer and say you think it’ll do well but you’re not sure and that you’re just having a little fun.

What do you think your answer will be if I asked you this same question right after you placed the bet? *

Instead of hedging, you’ll be far more certain that your horse is a winner because you placed a bet. You added finality to your decision.

Decision Finality

According to the cognitive dissonance theory, you become far more certain you are right about something if you can’t undo that decision.

Cognitive dissonance is a mental state of tension. It occurs when we hold two ideas, attitudes, beliefs, or opinions that are psychologically inconsistent with each other. We need to reconcile these two inconsistent beliefs to make ourselves feel better.

You’re not the type of person that frivolously throws money away, but you just gambled on a horse race. You need to self-justify these two conflicting actions and the one you decide on is increased confidence in your horse winning. You’re not throwing money away; you are going to get it back and more.

For this reason, if you’re considering a major purchase do not ask someone who recently bought the same item if it is the right thing to do. They need to reduce their own cognitive dissonance. They will try to convince you that the major purchase is the absolute right thing to do. Do this instead.

Therefore, if you want advice on what product to buy, ask someone who is still gathering information and is still open-minded. And if you want to know whether a program will help you, don’t rely on testimonials; get the data from controlled experiments. – From Mistakes Were Made (but Not by Me)

Decision Finality & Investing

There are two ways we add finality to our investment decisions. The first and most obvious one is the act of buying a position. We’re no longer in the betting line. We placed our bet. We probably think our investment is more of a sure thing than it is.

The second way we add finality is through this letter. We are putting our title as “expert” on the line by writing about why we think a stock is a good investment. If we’re wrong about an investment, we’re prone to compound the mistake to protect our ego.

But when an expert is wrong, the centerpiece of his or her professional identity is threatened. Therefore, dissonance theory predicts that the more self-confident and famous experts are, the less likely they will be to admit mistakes.

Prevention

How can we prevent ourselves from falling into these traps?

First, our day job is not one of public prognostication. So, there is little risk of ruining our public perception. We’re OK with being wrong and we’ll admit it.

Second, before investing in a new position we outline the main risks to our investment thesis and what would need to happen to make us say we were wrong. The tough part is then recognizing things went wrong. Regularly reviewing our investment thesis can provide an opportunity to see if things are going as planned

Third, we need to avoid the confirmation bias trap. If a well-known large investor has the same position as us, it’s OK for us to listen to their opinions and to agree with them but we need to be aware that they too are subject to self-justification. So, like the advice above, we need to listen more to those that are still researching and gathering information about our position and give more weight to what they have to say, good or bad.

Fourth, instead of competing to be the smartest investor out there, we focus on trying to avoid doing the dumb thing.

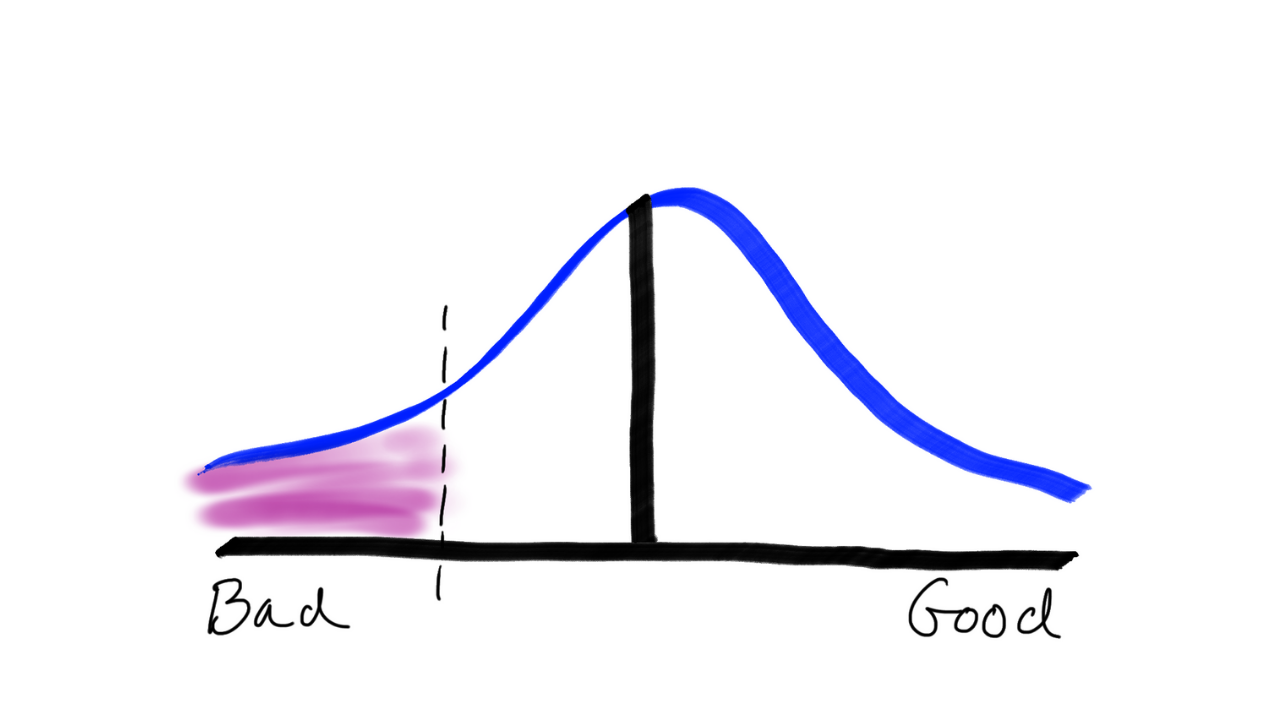

If decisions were a bell curve, dumbest on the left and smartest on the right, we want to eliminate the left tail. We hope that by eliminating the dumb stuff we increase our odds of doing the right thing.

Trying to be the smartest person also puts our reputation further on the line. It creates larger incentives to not admit our mistakes and it could lead us to make costly investment mistakes with your money. We’re surrendering to the idea that other people are much smarter than us. This reduces how much of our ego gets in the way of our investment process.

We don’t chase story stocks. We don’t invest in turnaround or distressed companies. We do not get involved in complicated corporate restructurings. Instead, we focus on investing in industry-leading companies with high returns on invested capital. We want companies with a competitive advantage that are in a secular growth trend. And then we want to pay a reasonable price for them.

We will be wrong at times. By constricting our investment choices, we’re lessening our ability to make a dumb decision. Hopefully, we increase our chances of positive investment outcomes.

*This scenario is from the book Mistakes Were Made (but Not by Me) by Carol Tavris & Elliot Aronson